Sporting stars often spring from humble beginnings. There’s a certain never-say-die attitude in working-class athletes that allows them, more often than not, to supersede their silver-spooned competitors.

Sporting stars often spring from humble beginnings. There’s a certain never-say-die attitude in working-class athletes that allows them, more often than not, to supersede their silver-spooned competitors.

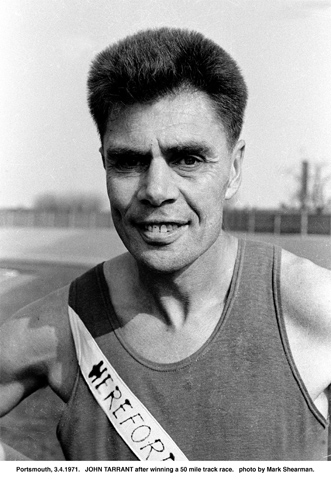

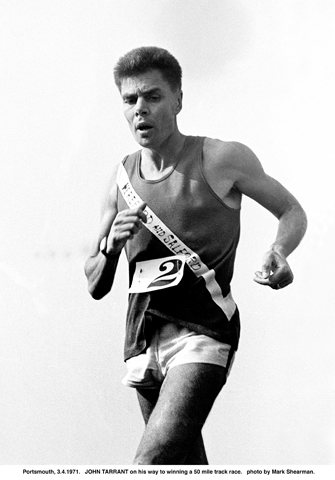

John Tarrant was no conventional athlete, but his determination to stick it to the privileged elite saw him capture the hearts of the labouring class and become a star in his own right.

Born in Shepherd’s Bush in 1932, Tarrant’s life got off to a tragic start. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was a child and, with his father fighting in the Second World War, John and his younger brother, Victor, were raised in a children’s home until his father was demobilised in 1945. When his father returned, he moved the family – John, Victor, and his new wife – away from the city to the sleepier surroundings of Buxton in the Peak District. However, their new life failed to bring renewed prosperity and John, now 18, turned to sport – specifically, boxing – for a helping hand.

It soon became clear, though, that the ring would be a source of beatings, rather than financial reward. He did compete regularly, in Buxton Town Hall – earning a grand total of £17 (around £264 in today’s money) – but his persistence with a sport that he had no real passion, or great talent, for was not based on the prize money; it was because boxing provided Tarrant with the opportunity to do something he was truly good at: running.

Accordingly, he gave up boxing and concentrated his efforts on distance running. Tarrant’s hope was to compete in the marathon at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. However, upon applying to join Salford Harriers, he chose to answer honestly to the question as to whether he had ever earned money from sport. Due to running’s strict amateur status at the time, Tarrant was immediately banned from competition for life.

Never give up

It was a Draconian sentence, delivered by men of “gentlemanly status” who were often wealthy enough not to work. Tarrant, though, was not one for giving up lightly. He continued to train – filling his backpack full of rocks and heading for the Derbyshire hills – and, with the assistance of his brother, began to gatecrash races. Much to the chagrin of the authorities and delight of the press, who anointed him as ‘The Ghost Runner’, Tarrant would often out-perform the recognised stars of the day.

By 1958, the authorities relaxed the banning order – with one crippling caveat. Tarrant would be allowed to compete in Britain but not for Britain. So with his Olympic dreams shattered, Tarrant turned his attentions to ultramarathons, setting world records for 40 and 100 miles.

During one such ultramarathon – the 90K Comrades in South Africa, in which he finished fourth – Tarrant became aware of the apartheid conditions in the country. Horrified by what he heard and keen to show solidarity with the anti-apartheid movement, he began to enter what had previously been ‘blacks-only’ races. Most notably, he went on to win the 80K Goldtop Stanger-to-Durban race in 1970. To this day, he is regarded as a hero in South Africa.

Tarrant, though, would not live to see that country united. He died of stomach cancer in 1975, at the age of just 42. Harshly treated in life and largely forgotten in death, Tarrant’s story is one of perseverance in the face of extreme adversity. In the spirit of hard, honest running, the Ghost Runner lives on.