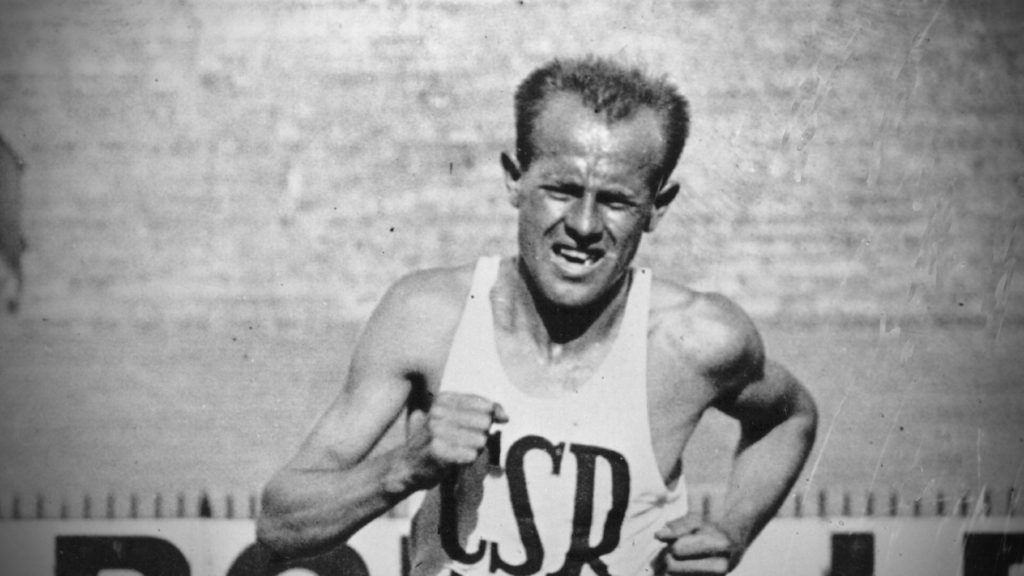

Born on 22 September 1922, the sixth child in a modest family, Emil Zátopek’s first job was in a local shoe factory. One day, the factory sports coach ordered his charges to run a race. Zátopek attempted to wriggle out of it but eventually finished second – thus kick-starting a lifelong love affair with running. His crowning glory came at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, where he won gold in the 5000m, 10,000m and Marathon – a feat never achieved before or since. But it was his behaviour off the track that won him even greater affection. He famously gave away his Olympic 10,000m gold medal to friend and rival Ron Clarke. “Great is the victory, but the friendship is all the greater,” as Zátopek once said.

Under the microscope

Heart

As someone who dominated distance running for a decade, you might expect Zátopek to be an extraordinary physical specimen. From a purely physiological perspective, however, he was fairly unremarkable. His resting heart rate was around 50 beats per minute (bpm). Mo Farah’s is, by comparison, 33bpm.

Arms

Described by one appalled observer as having the look of “a man wrestling with an octopus on a conveyor belt,” Zátopek’s arm action was about as unconventional as it gets. However, as he was quick to point out, races are not catwalks. “I shall learn to have a better style,” he said, “once they start judging races according to their beauty.”

Feet

Although he preferred to run in spikes on the track, the vast majority of Zátopek’s punishing training regime was conducted wearing army boots. These daily sessions, conducted alone in the woods close to his army base, would often take place in the foulest of weather. “There is a great advantage in training under unfavourable conditions,” he said. “It is better to train under bad conditions, for the difference is then a tremendous relief in a race.”

Head

Zátopek must rank as one of history’s most disciplined runners. While today’s track and field stars enjoy state-of-the-art facilities, the Czech trained alone in the woods next to his army camp. Here, he would put himself through workouts such as 50 x 400m. “It’s at the borders of pain and suffering that the men are separated from the boys,” he said.

Mouth

Zátopek was famous for conversing with his rivals during races. During the marathon at the 1952 Helsinki Olympics, he asked Britain’s Jim Peters if the blistering early pace might be a tad too quick. Peters, attempting to fool Zátopek, replied: “It isn’t fast enough.” Taking him at his word, Zátopek sped off for gold and Olympic glory. Peters didn’t finish.

Legs

From the waist up, Zátopek was a running coach’s worst nightmare. From the waist down, he was a dream. A snappy cadence, forefoot strike and good knee-lift were all present and correct. These good habits may have been honed by Emil’s unusual practice of putting a layer of his wet clothes at the bottom of his bath and running on them, like a one-man washing machine.

Train like Zátopek

■ Get sprinting

Zátopek is often credited as being the pioneer of interval training – short, sharp sprints repeated several times. The Czech took this to extremes, sometimes running 50 x 400m at close to his maximum speed. People at the time balked at Zátopek’s unusual training methods, but the results speak for themselves.

■ Embrace pain

Zátopek’s training methods were so brutal as to verge on masochism. That he trained alone in the woods wearing his army boots only made things harder. Zátopek felt pain like the rest of us; he just continually chose to push through it. “When it hurts to go, go faster,” he said. Are you brave enough to do the same?

■ Have a natter

Zátopek was a constant talker, known for striking up conversation in the middle of races. Having mastered a variety of languages, he would converse with his competitors in their native language, before sprinting away from them. Some thought this gamesmanship; more likely it was just Zátopek being friendly.