Depression is big business. And we’re not being facetious here – there are drugs companies, medical professionals and self-help gurus all around the world making their fortunes from other people’s suffering. But it’s also very real, and an agonising struggle for the millions of people who struggle with it every day.

It’s a growing problem, too, especially among young men. Suicide is the biggest killer of British males under the age of 50, with 100 taking their own lives every week. “Young men are three times more likely than women to commit suicide,” says Dr Gemma Trainor, a consultant nurse and specialist with young people who self-harm.

“And there’s a growing problem among men aged 40-50. Maybe their wives have lost interest, their children have grown up and left home, and they feel as if they’ve gone as far as they can in their careers. Depression is a big risk factor.”

Running, however, can do most things – and helping to overcome, or at least manage, depression is one of them.

THE SCIENCE

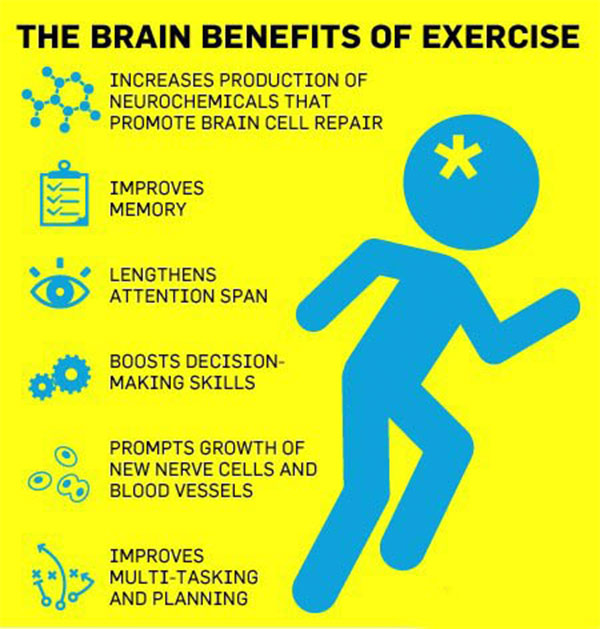

In a raft of studies, exercise – primarily in the form of, but not restricted to, running – has been shown to have several effects on the brain. It leads to the release of certain neurotransmitters in the brain that alleviate pain, both physical and mental.

Depression is related to low levels of certain neurotransmitters such as seratonin and norepinephrine, both of which can be stimulated by the effect of exercise on the sympathetic nervous system. Also important are endorphins: chemicals released by the pituitary gland in response to stress or pain, which bind to receptors in the brain’s neurons to inhibit pain and promote feelings of euphoria – more on that later.

Another positive side effect of running is a process called neurogenesis – the creation of new neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain that controls learning and memory. At a cellular level, it is possible that the mild stress caused by exercise stimulates an influx of calcium, which effectively ‘agitates’ proteins that promote the neurogenesis process. The upside is that exercise provides a natural trigger.

Running, in essence, can help fight the chemical imbalances that cause depression; a serious illness that can result in low mood, feelings of helplessness, self-harm and even suicide. “Depression can manifest itself in physical ways,” says Trainor. “You can suffer loss of energy, headaches, agitation or anxiety, and nutrition often suffers. There are also cognitive changes – loss of concentration, focus and confidence. Running can challenge all of these. GPs are able to prescribe gym memberships these days, and that’s because research has found that, in cases of mild or moderate depression, exercise is at least as effective as, if not more useful than, medication.

“It’s in severe cases of depression that medication may be required, day to day. But running can give you a sense of purpose and allow you to take control of your life.”

HIGH AND MIGHTY

So exercise is good for you, and the even better news is that running is just about the best form of exercise you can do. “It’s called the ‘runner’s high’ – we don’t hear the term ‘cyclist’s high’ or ‘rower’s high’,” says Andy Lane, professor of sports psychology at the University of Wolverhampton. “The reasons for this aren’t completely clear, but it’s likely that it’s because running is a movement humans learn naturally via walking as babies. It’s an extension of that natural movement pattern.”

At a very basic level, most of us can run – that is, physically put one foot in front of the other at a pace faster than walking. And you don’t have to flog yourself if you’re new to it. The key for beginners is not to overdo it. “Intensity is quite complex,” says Lane.

“If you’re unfit, running slowly is intense. Unfit people tend to start running at a high intensity and don’t enjoy it. Intense exercise triggers a response in the brain that says, ‘Careful, we can’t keep this up,’ and that message comes in the form of negative emotions – feeling miserable, sad and tired. Moderately intense exercise associates with positive mood.

“But once you reach a certain level, doing intervals or completing a hard session can bring a tremendous sense of achievement. Overcoming doubts and fears that you can’t cope builds resilience, and this can raise self-esteem.”

The benefits of running extend beyond the chemical reactions in your brain. It can help change bad habits and give a sense of achievement. “Sticking to a running programme is a form of exercising self-control, and self-control is a variable linked with a number positive attributes,” says Lane.

“Good self-control helps diet-management, job success, sticking to timetables and so on. Poor self-control is associated with a large number of societal problems such as anger and violence. Self-control is improved by training. People should run – it will lead to general happiness and, because of the physiological effects, reduces a whole host of cardiovascular diseases.”

There’s just one word of warning: if you’re taking medication, don’t bin it simply because you’ve pulled on a pair of running shoes and feel great about it. You should never come off medication without talking to your GP first.

“Depression is complex,” says Lane. “The causal link between exercise and mental health is not completely established, and exercise tends to help improve mood for those people who like exercising. People who dislike it and who are prescribed exercise might as well be given the worst-tasting medicine possible.”

RELATED: How to talk to someone about their mental health

Steve Clancey, 44, discovered that running could help him in 2009. “Over time, work pressures and life changes took their toll, and I was signed off in 2008 because I physically couldn’t work,” he says. “I saw a flyer to enter the London Marathon to raise money for Sense, the deaf and blind charity, and decided to do it on the spur of the moment. I didn’t particularly know what I was doing but I’d always been reasonably fit and entered some shorter events as part of my training.

“When I finished the marathon in four hours, in 2009, I was on cloud nine, and after the event I realised I missed it, so I joined a club and carried on.” The benefits were obvious. “It’s very therapeutic and training gives me a structure,” he says. “I also suffer from seasonal affective disorder so running makes the winter a lot more bearable, especially when I’m training for a race in the spring.

“Running has given me a focus. It’s improved my health and shown me it’s possible to improve at something. With running you get better little by little, and that shows you can overcome seemingly insurmountable problems by taking lots of small steps. I’ve met lots of new friends and I have a huge support network – there’s always someone to talk to,” adds Steve, who is a member of London’s Serpentine Running Club.

“In short, it’s something to look forward to, and a reason to get out of bed in the morning.” And that, when it comes to overcoming depression, is half the battle.