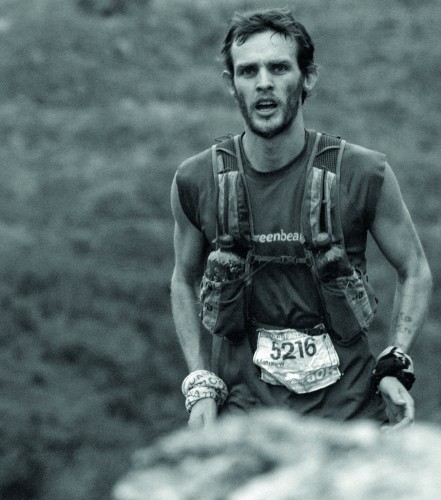

A loin-clothed Rapa Nui competitor runs with the sacks of bananas

Once upon a time, somewhere in Polynesia, there existed a faraway and troubled kingdom known as Hiva. One night, while the king was sleeping, he was visited in his dreams by a priest. The priest’s name was Hau-Maka and he showed the king a new promised land, safe from the disasters befalling his kingdom. Next morning the king sent his bravest and strongest scouts into the Pacific Ocean to find the land they would call Te Pito ‘o te Kāinga – The Centre of the Earth, known today as Easter Island.

Legend doesn’t say what hardships those scouts endured or where indeed the kingdom of Hiva was located. But wherever the first people of Easter Island came from, we can be sure they travelled at least 2,000K from the nearest land. They adventured by canoe and navigated by starlight – making this ancient journey one of the most incredible endurance feats the world has ever seen.

The locals, known today as the Rapa Nui, have an annual February festival called Tapati. It’s a cultural celebration of dance, drama, music, handicraft and, perhaps most importantly, sport. Was it possible that the athleticism of those ancient first arrivals still coursed through its modern day people? I knew I had to find out for myself.

Meeting the athletes

After a five-hour flight from Santiago, Chile I landed in the hot, wet streets of Easter Island’s only town, Hanga Roa. I had arrived in time for the first of the sports events – He Tau’a – a race that takes place beside an emerald green lake within a spectacular volcanic crater.

For the last four months, the athletes had dedicated themselves exclusively to training. They lived a hermit-like existence in a makeshift hut at the foot of the volcano. Their mornings were often occupied by collecting reeds to weave the boats they were to use during the race. Other times they would need to fish for food, hunting eels in the rock pools using mangai hooks traditionally made from the bone of a human hip. At midday they would train using sandbags to recreate the weight of the 20kg banana bunches they would carry while running. By night they would drink imported protein shakes and dream of success during the Tapati fortnight. It seemed an incredibly tough, macho existence with little space for family and children.

I saw the first competitor as he burst from the water, discarding his totora boat on the bank. Running barefoot and in only a loincloth, he charged towards the bananas – the shark tattoo on his leg gnashing its teeth back and forth with every powerful stride. The crowds screamed as he swung the cumbersome weight over his shoulders, the pulse of the Polynesian drumming becoming feverish.

Somewhere on the back straight, the runners each picked up a support runner who could be heard shouting encouragement as they closed the mile loop around the lake. As they discarded the fruit, the runners’ biceps quivered. An unburdened return leg remained to the far side of the lake on foot. Here they launched into the water on another reed craft, and hand-paddled back across. It was all over for the fastest athletes in just over 17 minutes.

Competitive instinct

Before the next event, I took the chance to explore the island on foot and find out more about the athletic history of the Rapa Nui. The obvious challenge was running up Maunga Terevaka, the island’s highest summit at 511m. Climbing its grassy flanks, I could see coastal trails weaving around the island and the famous Moai statues on the shore, backdropped by screens of white ocean surf. How these statues of up to 80 tonnes were dragged into place from the 12th Century onwards still baffles modern engineers. Some of the islanders claim a magical life force they call “mana” made them walk into position.

After a five-mile jog on a winding mountain, I found out more at the sacred stronghold of Orongo. Here in the 1700s, the Rapa Nui founded a new cult, worshipping muscle and testosterone in place of their ancestors represented by the Moai. Once a year, they would hold the Birdman contest. The strongest warriors from each tribe would run across jagged rocks, scramble down sea cliffs and then swim to the outlying island of Motu Nui. Several competitors died annually. But the first to successfully return from the island with the uncrushed egg of a sooty tern would be crowned king for the successive year. A sort of cross between Mortal Kombat and an Easter egg hunt.

let battle commence

Echoes of the Birdman competition can still be found in the warlike races held today. I watched a week later as body-painted runners assembled at the port shortly after sunrise. The shark tattooed runner was there, and out for blood after losing his advantage at the volcano run and finishing third. His team of runners were stretched out at 500m intervals along the island’s shore, dressed in loincloths and shiny new Nike trainers.

I pursued the runners by bicycle, jostled among grunting war cries and chasing mopeds. At the first changeover there was a police roadblock to stop car traffic, but chaos broke out as bikes and bananas clattered into the officers and vehicles.

The road then became quieter. Stray dogs joined us. Tourists were startled from their sea-view breakfast – the Rapa Nui a wave of lactic acid, bananas and body paint. Victory fell to the shark-tattooed runner’s team. His name, I had now learnt, was Hau-Maka. When the last of the runners had arrived, the Rapa Nui retreated to a cave set back from the finish where they could pick over the race and look out at the endless horizon.

I had been with Rapa Nui runners for almost two weeks. It was clear they were exceptional athletes. And yet, as I watched Hau-Maka gesture wildly and speak in Rapa Nui, I thought there was perhaps something about them I could never understand. A magic that belonged to Hau-Maka’s namesake, the priest. To the scouts who made the journey across the waves. And their descendants for generations ever after.

A Rapa Nui runner is followed by members of the press