“I finished a lot slower than expected and thought, ‘Something’s not right here.’” Irish ultrarunner John O’Regan had just completed a 10-mile race – a drop in the ocean compared to the mammoth distances he’s used to covering – and, as he rightly assumed, something wasn’t right: he had the early stages of Overtraining Syndrome, otherwise known as OTS.

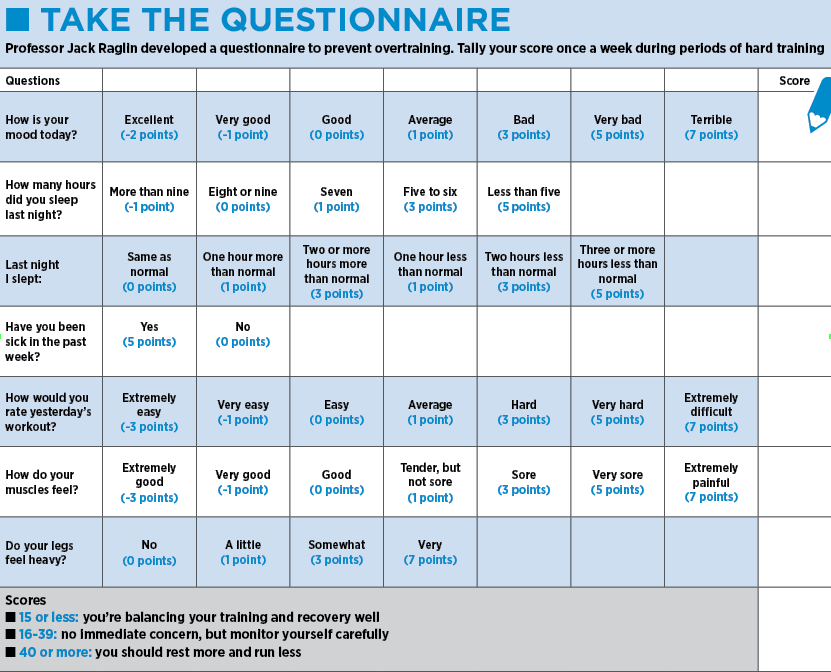

If, like me, your initial reaction to such a term is that it sounds like a convenient excuse for the work-shy, it’s important to garner a basic understanding of the science behind it. Jack Raglin, Professor of Kinesiology at Indiana University Bloomington, is an authority on the subject. “Overtraining syndrome is generally accepted to be a consequence of excessive training paired with inadequate recovery,” he says. “Its defining feature is a long-term loss in the ability to perform physically.”

As an international athlete, O’Regan had the advantage of knowing his body inside out. When he noticed his heart rate was significantly lower than expected after the 10-mile race, he went to see a sports doctor at Trinity College, who immediately recognised O’Regan’s poor performance and low heart rate as early signs of OTS. Thanks to addressing the issue early on, a few month’s later he went to the British 24-hour Championships and ran the best ever Irish debut for the format.

But what about the middle-of-the-pack runner? Your correspondent recently finished a 5K race close to 90 seconds slower than expected. I didn’t, however, rush to the nearest sports science lab; I ascribed my dip in performance to terrible pacing and taking the pre-race carbo-load to new levels of excess. The question to ask, then, is how can you tell if your poor performance is a sign of a more serious, underlying problem?

“Among the most common symptoms,” says Raglin, “are extreme muscle soreness, increased perception of effort, feelings of heaviness, and disturbances in sleep and appetite.” While an unusually high or low heart rate can also be an indicator – as in O’Regan’s case – it’s worth noting that heart rate can be affected by a number of factors – the mathematical prowess of Countdown’s Rachel Riley, for example – so other symptoms are more easily relatable to OTS.

Aside from the physical ailments, overtraining can also have a profound psychological impact. Raglin explains, “Depression scores increase more than virtually every other psychological measure we have used to test athletes, and the depression often reaches clinical significance where treatment of some sort is warranted.” Before you abandon a life of running, however, rest assured that most runners don’t train anywhere near enough to be at risk. “Generally,” says Raglin, “there will be little risk of OTS unless the training load is severe, but researchers have also acknowledged that poor recovery – nutrition, sleep, recreation, relaxation – is a key issue. “How the athlete feels after a night of rest, before the first training run of the day, is key,” Raglin continues. “Awareness of day-to-day fluctuations in feelings of tiredness and motivation is very important in identifying OTS.”

But what happens to those who ignore the signs?

Perhaps the most well known case of performance-destroying OTS is that of Alberto Salazar, now a world-renowned coach for reasons good and bad – Salazar is the head of Nike’s hugely successful Oregon Project, but is also facing serious allegations of doping. Between 1980 and 1984, Salazar set three American track records and won three New York Marathons in a row. His intense training schedule, however, brought his career to an abrupt end. After a 15th placed marathon finish at the Los Angeles Olympics, he spent the next decade in a downward spiral of respiratory infection and depression. By the time he eventually retired in 1998, the former golden boy of US athletics could barely run for half an hour.

For Raglin, OTS is an all-too-common problem among elite runners. “There is a culture of training among some of these athletes that massively accentuates the risk, namely their profound disregard for the importance of recovery and training periodisation, as well as the fact that they do not back off when serious symptoms start to occur.” But amateur runners also like to push the boundaries. After all, the only way to become a better runner is to continue to run quicker, further and harder.

Moreover, on the borders of OTS is a sweet spot known as ‘over-reaching’ – a deliberate, short-term period of excessive training followed by a period of rest. Many experts believe this can have significant performance benefits. During a period of over-reaching, athletes can experience symptoms almost identical to OTS, the difference being that, with over-reaching, athletes push themselves to the brink and then take at least two full days of rest.

The concept of overtraining, then, is a difficult one to define. While OTS can be serious enough to derail even the brightest of careers, there is no cut-and-dried definition of what constitutes overtraining. For the progress-hungry runner, hard work does, invariably, pay off. The key, though, is to listen to your body. If aching legs won’t recover or a poor night’s sleep turns in to a week of insomnia, take a look at your running schedule and ask yourself honestly, ‘Am I overdoing it?’

Are you at risk?